Turkey seeks to destroy Kurdish self-government in Syria – but it just might achieve the opposite effect

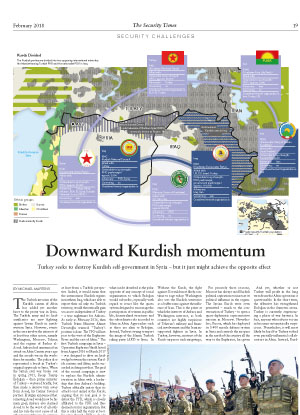

The Turkish invasion of the Kurdish canton of Afrin has added yet another facet to the proxy war in Syria. The Turkish army and its Arab auxiliaries are now fighting against Syrian Kurds in northwestern Syria. However, events in the area involve the interests of at least four other actors, namely Washington, Moscow, Tehran and the regime of Bashar al- Assad. Ankara had announced an attack on Afrin Canton years ago and the assault was in the works there for months. The policy also represented a break in Turkey’s original approach to Syria. When the Syrian civil war broke out in spring 2011, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan – then prime minister of Turkey – waivered briefly, but then made a decisive turn away from Assad, his former favored partner. Erdoğan announced that removing Assad would now be his main goal; Ankara also claimed Assad to be the worst of all evils and his rule the root cause of all other terrorist threats. In summer 2012, however, something happened in the Syrian theater of war that Ankara had not expected; the regime in Damascus largely withdrew its troops from its Kurdish areas in the north – troops it badly needed in other parts of the country. The Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its armed People’s Protection Units (YPG) subsequently took power there, proclaiming three Kurdish cantons: Jazira and Kobanî in the east and Afrin in the northwest. Since that moment, Ankara’s goal of bringing down Assad has been increasingly overshadowed by the fear of a “Kurdish threat.” Given the prospect of a permanently Kurdish-controlled region in the north of Syria, Assad was downgraded from Turkey’s main enemy to a second-tier menace. What Ankara now feared most was that the Kurds would be able to establish a land connection between the two cantons in the east and Afrin in the west. If the Kurds also succeeded in gaining access to the Mediterranean from Afrin, it would jeopardize the balance of power in the Middle East, at least from a Turkish perspective. Indeed, it would mean that the autonomous Kurdish regions in northern Iraq, which are able to export their oil only via Turkish territory, would theoretically gain sea access independent of Turkey – a true nightmare for Ankara. As early as February 2016, then Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu warned: “Turkey’s position is clear: The YPG will not pass to the west of the Euphrates River and the east of Afrin.” The first Turkish campaign in Syria – Operation Euphrates Shield lasted from August 2016 to March 2017 – was designed to drive an Arab wedge between the eastern Kurdish cantons and Afrin; and it succeeded in doing just that. The goal of the second campaign is now to replace the Kurdish administration in Afrin with a leadership that does Ankara’s bidding. Turkey officially insists that its attack is not aimed at the Kurds, arguing that its real goal is to defeat the PYD, which is closely affiliated to the PKK and thus deemed a terror organization. But this is only half the story at best. It is true that the PYD is closely linked to the PKK in terms of ideology and personnel. In the 1980s, then Syrian ruler Hafez al-Assad permitted PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan to wage his war against the Turkish state from a base in Syria. During this time, the PKK gained a lot of momentum from Syrian Kurds, in particular in Afrin. It is also true that the PYD is a Syrian offshoot of the PKK. However, two other facts serve to considerably weaken the Turkish argument. First, the Syrian Kurds – unlike the PKK – never carried out attacks on representatives of the Turkish state. Second, statements by Turkish politicians have made it clear that their goal is not only the dissolution of PYD/YPG rule in Afrin, but indeed the abolishment of any form of Kurdish self-government whatsoever, no matter who is in charge. Ankara’s approach is motivated by a desire to avoid a repeat of the “first sin” of Kurdish autonomy as it exists in Iraq.

The conflict also has an ideological component that is often overlooked: The sociopolitical model of the Kurds in Afrin represents what can be described as the polar opposite of any concept of social organization to which Erdoğan would subscribe, especially with regard to issues like the quota system designed to encourage the participation of women in public life, decentralized structures and the subordinate role accorded to Islam in Afrin. Approaches such as these are alien to Erdoğan. Instead, Turkey is trying to export the image of the Islamic Turkish ruling party (AKP) to Syria. In other words, Turkish tanks are also carrying Erdoğan’s ideas with them. This means that a country only recently praised as a democratic model for the Middle East has now become an exporter of autocracy.

Turkey is also eager to generate a factsheet for a regional post-war order. In this sphere, however, it comes up against a complicated web of strategic interests held by the other players involved in Syria. The United States was previously allied with the Syrian Kurds. Indeed, the YPG was the Americans’ most effective ground force in the fight against the Islamic State, which, until last year, was considered the greatest threat in the region. Without the Kurds, the fight against IS would most likely continue to rage today. Washington also sees the Kurdish territories as a buffer zone against the influence of Iran. This is the point at which the interests of Ankara and Washington intersect, as both countries are highly suspicious of Teheran’s military and financial involvement and the Iranian-supported fighters in Syria. In Turkey, however, mistrust of the Kurds surpasses such misgivings, especially as their interests intersect with those of Iran in this case; indeed, Iran also has a Kurdish minority, and Tehran sees the suppression of any efforts by the Kurds to form self-government as one of its many raisons d’état. In a certain sense, the Kurds are the only link between Ankara, Tehran, Baghdad and Damascus – nobody wants to give the Kurds anything.

For precisely these reasons, Moscow has always used Kurdish political aspirations to increase its political influence in the region. The Syrian Kurds were even permitted – much to the consternation of Turkey – to open a quasi-diplomatic representative mission in Moscow. Nevertheless, Russia, which has deployed its S-400 missile defense system in Syria and controls the airspace in the north of the country all the way to the Euphrates, has given the green light to Turkey’s Operation Olive Branch. For Moscow, the Turkish offensive has two advantages. First, it exacerbates the long-smoldering conflict between Ankara and Washington; indeed, Russia would never pass up an opportunity to deepen the rift between two NATO partners. Second, a Turkish attack on Afrin might possibly drive the distressed Kurds back into the arms of Russia’s protégé Assad. Divide NATO and strengthen Assad – in Moscow’s zero-sum logic, this would be a double victory. In the meantime, the Kurds would once again be made to feel that they are nothing more than small change in the grand bartering system of the major powers.

And yet, whether or not Turkey will profit in the long term from the Afrin operation is questionable. In the short term, the offensive has strengthened Erdoğan in the domestic arena. Turkey is currently experiencing a phase of war hysteria. In fact, anyone who refuses to join in becomes automatically suspicious. Nonetheless, it will most likely be hard for Turkey to find even partially influential collaborators in Afrin. Instead, Kurdish terrorism will undoubtedly gain new momentum. Indeed, for at least five decades, Turkey has learned the bloody and recurring lesson that the terror carried out by the Kurds and Kurdish aspirations for self-government cannot be repressed simultaneously in the long term. Turkish politicians have been threatening for years that they will never permit the emergence of a “terror corridor” in Syria. However, Turkey’s intervention in Afrin might just have the opposite effect; it may lead to the creation of precisely such a “terror corridor.” That is, of course, if Turkey continues its attempt to combat this possibility by military means alone.

MICHAEL MARTENS

is a correspondent for Southeast Europe and Turkey at the German daily newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.