State of a state

The dispute between Kosovo and Serbia calls for more active European diplomacy

The tenth anniversary of the 2013 Brussels Agreement, one of the triumphs of European diplomacy, should have been celebrated with considerable fanfare. Instead, tensions between Serbia and Kosovo have chiseled away at many of the achievements of the past decade, diluting what hope existed for a comprehensive deal normalizing their relations. With the glue of the EU having lost some of its stickiness – not least for Belgrade – there are profound concerns about Russian and other influences in the still-fractured Western Balkans. The war on Europe’s eastern flank has made a deal between Belgrade and Pristina as pressing as ever.

Late 2022 saw the mass resignation of Serbs from Kosovo institutions in Pristina and the north, ostensibly in response to Kosovo’s steps to end the use of license plates issues by the Republic of Serbia. Ministers and mayors were followed by police, judges, prosecutors, local government employees and others. Many have vowed privately never to return, even those who once spearheaded the integration process. It constitutes one of the most profound setbacks for the normalization of relations between Belgrade and Pristina.

The resulting security vacuum prompted Pristina to deploy additional members of the Kosovo Police’s Special Operations Units, replete with tactical gear and long-barreled weapons, whose presence in the north had already fueled tensions for over a year. There have been frequent reports of harassment and intimidation, with claims that there are secret lists of those slated for arrest. Several police patrols have been subject to armed attack, with local elections postponed until spring due to the current situation. The construction of new police bases on expropriated land has further antagonized Serbs in the north. The arrest of an ethnic Serb former member of the Kosovo Police in December 2022 sparked the erection of new barricades throughout the north. Though their removal was ultimately negotiated before year’s end, the situation remains tense.

The smorgasbord of issues that have driven conflict – vehicle license plates, the acceptability of ID cards, the deployment of specific police units – are symptoms of a deeper underlying problem; namely a fundamental disagreement over Kosovo’s status fifteen years on from its declaration of independence. Under the shrewd stewardship of its Special Representative for the Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue, Miroslav Lajčák, the EU has created momentum around a much-heralded compromise from an almost standing start, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine further focusing minds. The belief that a vital window of opportunity – ending at next year’s US presidential elections – now exists to strike a deal has been widely embraced in Brussels and Washington, whose partnership has been much enhanced of late. Both incumbents in Serbia and Kosovo enjoy a firm political base on which to sell any deal, even if they remain reluctant to prepare their citizens for further unpopular concessions.

The foundations for a possible agreement, however, are perhaps flimsier than they were some twelve months ago. Relations between the two parties have deteriorated markedly, both in Brussels and in north Kosovo. There continues to be an absence of sustained high-level dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina, with the two parties largely dependent on shuttle diplomacy. Various agreements struck under the European umbrella either remain unimplemented or have completely unraveled, despite the EU reiterating that all previous commitments must be honored. Little has happened of late to build the requisite confidence and trust between the respective parties.

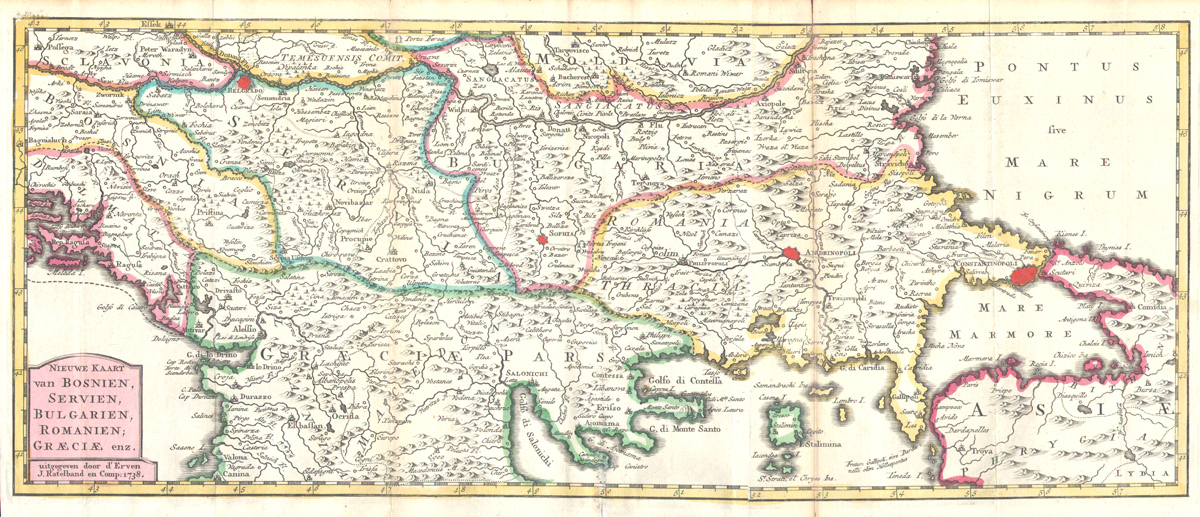

Mapping it out: Ratelband map of the Balkans from 1738

Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić has conditioned the return of Kosovo Serbs to Kosovo institutions on the establishment of the Association/Community of Serb majority municipalities (A/CSM), one of the founding elements of the Brussels Agreement. Kosovo has thus far refused to budge, despite mounting pressure from the EU and US. Though a 2015 Constitutional Court verdict that deemed various provisions unconstitutional is frequently invoked, that very same ruling states that the A/CSM must be established. More emotive narratives have since emerged, with the A/CSM being compared to the Republika Srpska, the entity in Bosnia-Herzegovina that regularly flirts with secession. While Belgrade is pushing for the A/CSM to be created prior to any deal, Pristina is striving to roll such commitments into a comprehensive agreement that would include mutual recognition.

The said EU proposal, which is yet to be published but has been leaked at various junctures, allegedly mentions the “inviolability of borders and respect for territorial integrity” and a commitment to develop “good neighborly relations,” entailing the mutual recognition of “relevant documents and national symbols.” It is understood to reference the principles of the UN Charter, including those pertaining to the sovereign rights of states, and apparently specifies that none of the parties “can represent the other party in the international sphere or act on its behalf.” Furthermore, Serbia would not oppose Kosovo’s membership in any international organization, while both parties would commit to exchanging permanent missions.

While the deal offers Kosovo some consolidation of its statehood, it does not and cannot guarantee a shift in the stance of the five EU non-recognizers (Spain, Greece, Cyprus, Romania and Slovakia). Some bilateral or other subsequent process will be required. The hope (rather than expectation) is that once one of these dominoes has fallen, the rest will follow suit. Although it offers Pristina a clearer pathway toward membership in the EU and NATO, it fails to offer the guarantees they would have wished for, especially given the veto that any EU member can enact at various junctures along the way. Pristina, therefore, must take a leap of faith to accept a deal that doesn’t provide for mutual recognition by Serbia, yet opens up the prospect of a smoother path towards international recognition. In such an uncertain geopolitical environment, there are understandably profound concerns in Pristina, which would like the issue resolved once and for all.

For Serbia, the absence of formal mutual recognition is being tentatively presented as a success – a compromise agreement that seemingly unlocks the country’s EU perspective while not requiring that it de jure recognize Kosovo’s independence. The fundamental impediment for both parties, however, is the stretching and diluting of the very EU accession process that could incentivize compromise. Investing in concessions now brings only limited returns in the short term. Incumbents fear that it will be their ultimate successors who reap the benefits. A more tangible prospect of accession would eliminate such nagging doubts. While there is more of a buzz about enlargement in Brussels – driven primarily by Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova long with Bosnia-Herzegovina’s candidacy and Kosovo’s membership application – it does not resonate in the Western Balkans. Reform processes have stalled and bilateral disputes remain unresolved. Politicians are doing little to persuade Europe to open its arms.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has further raised the stakes, with each party grappling to blame the other for a lack of process. Old memories have been reawakened. Contemporary events are increasingly defined and interpreted through the prism of war. Some voices are more nervous, others more bombastic. Serbia’s refusal to join the EU’s sanctions regime against Russia – despite publicly denouncing the war and supporting Ukraine’s territorial integrity – only adds to the uncertainty, especially given the vitriol of its tabloids. The prospect of localized outbreaks of violence in Kosovo cannot be entirely excluded, and the international community will need to reinforce and maintain its security presence. Those in Brussels and elsewhere struggle to comprehend such spikes in tension while there’s a war on in Europe.

A deal between Belgrade and Pristina would lay firm foundations for a full-fledged normalization of relations further down the road when both Serbia and Kosovo would ideally be on the verge of EU membership. Such black and white confrontations of sovereignty inevitably require some resort to various shades and smudges of grey, to the frustration of many. The deal outlined by the EU offers not only clean lines but vibrant colors and prospects. It clarifies the key points of dispute and delineates clear approaches to defusing them while offering a framework of incentives to underpin and reinforce the process. In doing so, it can simultaneously break the shackles of disputed statehood and calm the course of integration of Kosovo’s Serbs. It may not enshrine mutual recognition at this stage, but it offers legally binding mutual acknowledgement and respect. At this juncture, such a compromise in Europe is more vital than ever.

Ian Bancroft is a writer and former diplomat based in the Western Balkans. He is the author of Dragon’s Teeth: Tales from North Kosovo

Credit: picture alliance / Liszt Collection