United we stand,divided we fall

Relations between Europe and the United States have never been just a pleasant walk in the park. The transatlantic partners have had many passionate agreements; intermittent laments about an increasingly broad “rift,” “chasm,” “gulf” are nothing new. But never before has the danger of actual divorce been more real than after the inauguration of Donald Trump.

Over the past seven decades the allies quarreled about Mannesmann pipes to Russia and about Germany’s policy of détente. They wrangled over inflation rates and nuclear strategy, about bananas, chickens and beef, Iraq and Guantanamo. And they had acrimonious disputes over disarmament and climate change. Yet they never parted ways. Their feuds were family spats: angry outbursts quickly ending with no hard feelings. Realizing that Americans and Europeans have more in common with each other than with anyone else in the world, they learned to live with their differences. Their historical, cultural and philosophical similarities and affinities constituted a powerful link. Even where their interests occasionally diverged, their community of values remained a firm basis of European-American togetherness.

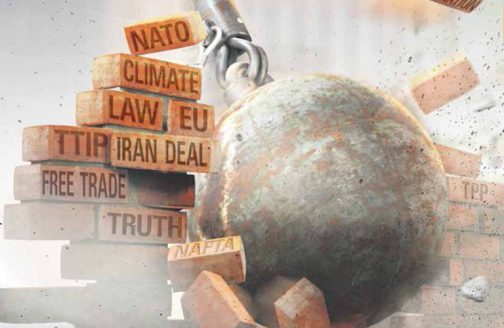

Now Trump seems to be turning his back on the fundamentals of American democracy: rule of law, separation of powers, freedom of opinion. In the process he is abandoning the basic principle of US foreign policy, taken as a given since the end of World War II: the firm belief that America’s alliances immensely increase America’s security. He does not see a connection between alliances and security. Europe, in his view, is expendable. He considers Brexit a “great thing,” and he thinks – and favors – that others will leave the EU, pointedly adding: “I don’t care whether it’s separate or together, to me it does not matter.”

Small wonder that Europeans are aghast – with the exception, of course, of illiberal democrats such as Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Poland’s Jarosław Kaczyński and anti-EU right-wingers like Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders and Frauke Petry. Europe’s Donald – Donald Tusk, the Polish president of the European Council – gave vent to the feeling of the vast majority of his fellowcontinentals, politicians and pundits alike in a remarkably straightforward letter to the EU heads of state or government.

Dealing with the threats facing Europe today, Tusk listed first “the new geopolitical situation in the world and around Europe – an increasingly assertive China, especially on the seas; Russia’s aggressive policy towards Ukraine and its neighbors; war and terror in the Middle East and in Africa, with radical Islam playing a major role.” He then referred unabashedly to “worrying declarations by the new American administration.” All of these developments make Europe’s future highly unpredictable, he argued: “Particularly the change in Washington puts the European Union in a difficult situation; with the new administration seeming to put into question the last 70 years of American foreign policy.”

Donald Tusk’s central message was that in a world full of tension and confrontation, what is needed is courage, determination and the political solidarity of Europeans: “Let us show our European pride… Today we must stand up for our dignity, the dignity of a united Europe – regardless whether we are talking to Russia, China, the US or Turkey.” Europe should not abandon its role as a trade superpower; it should also firmly defend the international order based on the rule of law; and it should not surrender to those who want to weaken or invalidate the transatlantic bond. His trenchant final point reads: “We should remind our American friends of their own motto: United we stand, divided we fall.”

Other EuropRelations between Europe and the United States have never been just a pleasant walk in the park. The transatlantic partners have had many passionate agreements; intermittent laments about an increasingly broad “rift,” “chasm,” “gulf” are nothing new. But never before has the danger of actual divorce been more real than after the inauguration of Donald Trump. Over the past seven decades the allies quarreled about Mannesmann pipes to Russia and about Germany’s policy of détente. They wrangled over inflation rates and nuclear strategy, about bananas, chickens and beef, Iraq and Guantanamo. And they had acrimonious disputes over disarmament and climate change. Yet they never parted ways. Their feuds were family spats: angry outbursts quickly ending with no hard feelings. Realizing that Americans and Europeans have more in common with each other than with anyone else in the world, they learned to live with their differences. Their historical, cultural and philosophical similarities and affinities constituted a powerful link. Even where their interests occasionally diverged, their community of values remained a firm basis of European-American togetherness. Now Trump seems to be turning his back on the fundamentals of American democracy: rule of law, separation of powers, freedom of opinion. In the process he is abandoning the basic principle of US foreign policy, taken as a given since the end of World War II: the firm belief that America’s alliances immensely increase America’s security. He does not see a connection between alliances and security. Europe, in his view, is expendable. He considers Brexit a “great thing,” and he thinks – and favors – that others will leave the EU, pointedly adding: “I don’t care whether it’s separate or together, to me it does not matter.” Small wonder that Europeans are aghast – with the exception, of course, of illiberal democrats such as Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Poland’s Jarosław Kaczyński and anti-EU right-wingers like Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders and Frauke Petry. Europe’s Donald – Donald Tusk, the Polish president of the European Council – gave vent to the feeling of the vast majority of his fellowcontinentals, politicians and pundits alike in a remarkably straightforward letter to the EU heads of state or government. Dealing with the threats facing Europe today, Tusk listed first “the new geopolitical situation in the world and around Europe – an increasingly assertive China, especially on the seas; Russia’s aggressive policytowards Ukraine and its neighbors; war and terror in the Middle East and in Africa, with radical Islam playing a major role.” He then referred unabashedly to “worrying declarations by the new American administration.” All of these developments make Europe’s future highly unpredictable, he argued: “Particularly the change in Washington puts the European Union in a difficult situation; with the new administration seeming to put into question the last 70 years of American foreign policy.” Donald Tusk’s central message was that, in a world full of tension and confrontation, what is needed is courage, determination and the political solidarity of Europeans: “Let us show our European pride… Today we must stand up for our dignity, the dignity of a united Europe – regardless whether we are talking to Russia, China, the US or Turkey.” Europe should not abandon its role as a trade superpower; it should also firmly defend the international order based on the rule of law; and it should not surrender to those who want to weaken or invalidate the transatlantic bond. His trenchant final point reads: “We should remind our American friends of their own motto: United we stand, divided we fall.” Other European actors have been less constrained in their remarks. They are shocked by the world President Trump seemingly wants to build: a world in which it is eternally High Noon; where “deals” are recklessly pushed through; where multilateralism is heedlessly thrown out of the window in favor of bilateralism; and where allies and alliances are treated with contempt. They are upset by Trump as he defends torture, attacks the press, denigrates the judiciary, detests “this extremely expansive climate bullshit” (Trump’s words) and despises the international institutions the US created after World War II as the scaffolding of a peaceful and prospering international order. “America’s allies are worried – rightly so,” writes The Economist. They are worried, indeed, by the blatant lies (“alternative facts”) spread by the president and his entourage, by his habitual belittling of critics and intimidation of partners, by his naïve assumption that he can govern viaean actors have been less constrained in their remarks. They are shocked by the world President Trump seemingly wants to build: a world in which it is eternally High Noon; where “deals” are recklessly pushed through; where multilateralism is heedlessly thrown out of the window in favor of bilateralism; and where allies and alliances are treated with contempt. They are upset by Trump as he defends torture, attacks the press, denigrates the judiciary, detests “this extremely expansive climate bullshit” (Trump’s words) and despises the international institutions the US created after World War II as the scaffolding of a peaceful and prospering international order. “America’s allies are worried – rightly so,” writes The Economist. They are worried, indeed, by the blatant lies (“alternative facts”) spread by the president and his entourage, by his habitual belittling of critics and intimidation of partners, by his naïve assumption that he can govern via ceaseless Twitter barrage and by executive orders imposed out of the blue – circumventing the government apparatus and even his cabinet ministers. And they are worried, last but not least, by indications that hemight precipitate currency wars and trade wars, and even go to real war, inadvertently or with full intent, against Iran, North Korea or even China. Asked by The Times and Bild, in reference to his German grandfather, whether there was anything typically German about him, Trump answered: “I like order. I like things to be done in an orderly manner.” The mayhem he created with his Muslim ban belies this selfdescription; insouciance coupled with incompetence produced a chaotic mess.

In Germany, only the rightwing AfD (Alternative for Germany) had any kind words to say about President Trump. Volker Perthes, the director of the German Institute of International Affairs (SWP), said that Trump’s victory represents a hard knock for the West’s normative hard rock of liberalism. Sigmar Gabriel, the former SPD chairman and Berlin’s new foreign minister, was far more blunt: “Trump is the trailblazer of a new authoritarian and chauvinist international movement.” Martin Schulz, his successor as chairman of the Social Democrats and now the candidate for the chancellorship, put it no less explicitly: “If Trump keeps running with the wrecking ball through our value system, then we have to say clearly: That is not our policy.” Chancellor Angela Merkel phrased the same idea a bit more discreetly but, in its subtlety, just as unmistakably. Congratulating Trump on his election victory, she set out the values Germany and America share: “democracy, freedom, respect for the rule of law and the dignity of each and every person, irrespective of their origin, skin color, religious creed, gender, sexual orientation or political views.” On the basis of those values – and only on the basis of those values – she offered him close future relations. It was as much a warning as a welcome. The shock waves of regime change in Washington are shaking the world. The Europeans hope very much that the transatlantic relationship will survive the present tremors. But they realize full well that this requires finally overcoming their divisions and hesitations. In his philippic, Donald Tusk outlined what it would take: “a definite reinforcement of the EU’s external borders; improved cooperation of the services responsible for combating terrorism; an increase to defense spending; strengthening of the EU as a whole as well as better coordinating individual member states’ foreign policies.” It is a tall order. Europe is still battered by the global finance crisis, the refugee crisis and the Brexit crisis. But the Trump presidency could be a wake-up call: the Europeans’ last chance to get their act together. It is also the only chance to convince the new US president that the alliance with the Old World is worth saving and to end the spiral of distrust and discrimination that, unstopped, would spell the end of the West.