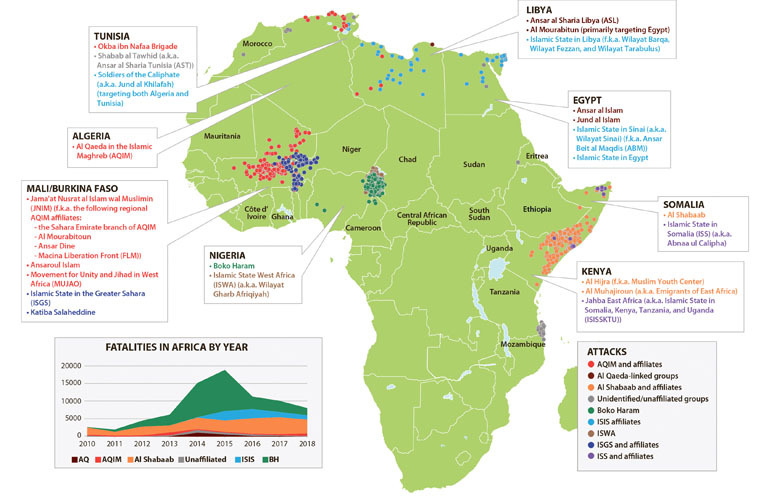

Terror, old and new: In Africa, militant groups swearing allegiance to the Islamic State are multiplying.

On Dec. 21, 2018, the declaration of war came from an unexpected source: “A so-called Islamic State has appeared in our country,” it said. “We have been observing its dangerous behavior for a time in the hope that it would change, but this has not taken place.” The speaker was Ali Rage, leader of Al Shabaab – the biggest Islamist terrorist militia in Africa.

According to estimates by the US Military Academy at West Point, Rage commands at least 4,500 fighters in Somalia. For more than ten years, they have controlled large parts of the country in the Horn of Africa. They are being opposed by the 22,000 troops of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), chiefly in the capital Mogadishu. Yet Rage’s call to “eradicate the cancer” and “defeat the disease” was aimed not at these forces, but at the perhaps 150 militants who, in Puntland in northern Somalia, had founded the “Islamic State in Somalia.”

Just before Rage’s statement, the group’s members had shot 14 Al Shabaab fighters and then posted a video of the deed online. It was a deliberate provocation that demonstrated how much power the IS cell now wields in Somalia. It is believed to have carried out 39 attacks in just the first seven months of 2018.

When Abdulqadir Mumin swore allegiance to IS and its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in October 2015, he had fewer than two dozen fighters by his side. He recruited the rest of his force from the dissatisfied inhabitants of his sanctuary, the Galgala mountains, and perhaps among former Somali pirates.

In late October 2017, some 50 IS fighters unexpectedly attacked and captured the port city of Qandala on the Gulf of Aden. It took government forces two months to retake the city. However, the spectacular operation failed to earn the hoped-for official recognition by al-Baghdadi.

The rise of IS in Somalia is no isolated phenomenon. West Point’s Jason Warner and Charlotte Hulme of Yale estimated in August 2018 that more than 6,000 men are currently fighting in Africa under the black banner of IS. More than half of them, some 3,500, are thought to belong to “Islamic State’s West Africa Province” or ISWAP. ISWAP spread fear and destruction in northern Nigeria under its previous name Boko Haram. In March 2015, the terrorist group’s leader Abubakar Shekau swore allegiance to IS and received official recognition. Not least because of his extremist methods, which are too brutal even for other terrorists and have caused hundreds of thousands of Muslims to flee their homes and undermine the IS strategy of territorial control, IS appointed Abu Musab al-Barnawi as successor to Shekau in August 2016.

Since then, both groups have been fighting against the Nigerian army as well as each other. Shekau’s faction is the smaller of the two, with an estimated 1,500 men. The other, ISWAP, has carried out a deadly offensive in recent months, killing hundreds of Nigerian soldiers. With each attack, ISWAP captures more weapons, vehicles and other military hardware.

Journalists on the ground claim that government troops no longer leave their bases for fear of resurgent IS fighters. There are reports of revolts against the army leadership. As half of all Nigerian troops have been committed to the antiterrorism campaign, soldiers are not rotated. Some elite troops have been fighting in northern Nigeria nonstop for two years or more against the Islamists, who are threatening to gain the upper hand under their new label, ISWAP. The army, meanwhile, is short on arms and munitions and, most importantly, its morale is suffering, says one military analyst in Nigeria.

Another Islamic State cell is fighting in Mali. It was founded in May 2015 by Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, former second-incommand of the militant group Al-Mourabitoun, which carried out an attack on a restaurant in Bamako in March 2015 and, in November of that year, took 170 hostages in the city’s Radisson Blu hotel. Two months later, Al-Mourabitoun operatives stormed two hotels in Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou. In January 2017, the group claimed responsibility for an attack on a Malian military base in Gao in which 77 people were killed.

Gao is also the location of the German military’s regional base. Al-Mourabitoun is among its most dangerous adversaries, yet the group does not belong to the IS network – shortly after al-Sahrawi pledged allegiance to IS, Al-Mourabitoun’s founder and leader Mokhtar Belmokhtar denounced al-Sahrawi, saying the latter had spoken for himself only. The number of fighters who then left Al-Mourabitoun to fight for the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) is estimated at just over 400. Al-Mourabitoun, which since March 2017 has been part of the Nusrat al-Islam network or GSIM, is at least twice as strong in terms of numbers. Still, al-Sahrawi’s IS cell has gained prominence with attacks, including one in September 2016 in the border region of Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali. In October 2017, its fighters killed four members of a US anti-terrorism unit.

African terrorist groups have their origins in the regions where they operate. The reasons that IS has managed to spread through Africa as the secondgeneration of global-branded jihadism are also peculiar to the region. One of the most important of these is that Al Qaedaaffiliated groups such as Al Shabaab and GSIM, and their forerunners, have now become somewhat of a “terrorist establishment.” Nearly two decades after 9/11, the power structures of these once-revolutionary groups have taken root.

In Somalia, Al Shabaab shares revenue from illegal commerce with the state and units of the AMISON mission, which are actually there to fight the militants. Rage’s fighters are less interested in establishing a caliphate than in getting rich. Trafficking charcoal and sugar, taxation and tolls on the distribution of humanitarian aid generate millions of dollars in annual revenue for these groups in Somalia. Al Shabaab is an established partner in a system of mafia-like patronage that divides the spoils of illicit activities among the most powerful.

Trafficking cigarettes, drugs, arms and (not least) migrants is likewise a lucrative business in the Sahara. This business is controlled primarily by the militant groups with changing names centered around Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a trafficking kingpin nicknamed Mr. Marlboro. In this sense, the founding of IS cells by Abdul Qadir Mumin in Somalia and Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi in Mali was also a rebellion against the established elite at a time when IS was at its territorial zenith, stretching from Palmyra in Syria to Ramadi in Iraq.

The Islamic State brand name, seen and heard throughout the world’s media, guaranteed maximum fear among populations and enormous attractiveness among fighters. At the time, both factors probably helped persuade Abubakar Shekau to place himself and his Boko Haram group at the service of IS.

For civilian populations, the growing popularity of the IS in Africa is a disaster. As demonstrated by Al Shabaab’s declaration of war against the Somali IS cell, the establishment Islamists will not give up without a fight. In the propaganda struggle, the two camps will likely seek to outdo one another with the most spectacular terrorist attacks possible while avoiding any sign of straying from Islamist doctrine.

An early victim of this development could well be Mauritania, a West African state that Al Qaeda operatives blanketed with a wave of attacks between 2007 and 2011. Since then, the country has remained astonishingly peaceful while militant attacks have ravaged neighboring Mali and other Sahel states. A note released by US intelligence that Algeria’s Al Qaeda leadership supposedly wrote to Osama bin Laden provides one possible reason: It says that Mauritania’s government has been paying between €10 and €20 million a year in protection money to the terrorist network.

Whether the note is genuine remains unclear, yet its publication appears to have put pressure on Al Qaeda. In May 2018, the group issued a call for attacks that explicitly singled out Mauritania.

MARC ENGELHARDT

spent many years reporting from Africa and is now a UN correspondent in Geneva. His book Weltgemeinschaft am Abgrund: Warum wir eine starke UNO brauchen (Our world community on the brink. Why we need a strong UN) was published in 2018.