wHim

Credit: shutterstock/Lemberg Vector studio

Credit: shutterstock/Lemberg Vector studio Afghan women have been forced to adapt to fluctuating, male-dictated dress codes for over 100 years

I’ve always been fascinated by the words of Fyodor Dostoevsky. One line, in particular, has stayed with me for years. In his novel Poor Folk, he says something to the effect of: “The degree of man’s freedom is directly related to his spiritual greatness.” I would like to slightly modify this weighty sentence and apply it to the situation of women in Afghanistan, whereby it would read something like this: “The degree of women’s freedom is directly related to the prevailing whim of men in this country.” In fact, those who hold power in Afghanistan – most of whom are men – have, at times, lowered this bar low enough to crush the bones of Afghan women. From time to time, they’ve also been known to raise the bar out of Afghan women’s reach.

For women in Afghanistan, the word freedom is used not in its proper sense, but rather as a cliché to describe females who’ve strayed a bit too far from strict traditional norms. “So-and-so is free,” people will say, referring primarily to the way she is dressed. Women who wear shorter hemlines or tighter, European-style clothing are described as being free, thereby implying that they lack modesty and propriety. For most people in Afghanistan, a “respectable” woman will wrap herself in a chador or cover herself from head to toe in black clothing and never wear makeup.

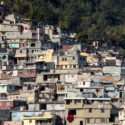

The clothing worn by women in Afghanistan and the extent of women’s political participation in that country have long since functioned as determinants of political success and the perpetuation of patriarchal authority. Starting with the reform-oriented ruler Amanullah’s ascension to power in 1919, women in Afghanistan have been subjected to a series of fluctuating decrees dictating how they should dress. In 1927 and 1928, Amanullah traveled abroad, visiting different countries in Africa, Asia and Europe. In the course of these journeys, he became an enthusiastic follower of modern European culture, ultimately concluding that successful social reform would be impossible without the presence and participation of women. Immediately upon his return to Afghanistan, he granted women access to social and political spheres and eventually called on them to remove their chadors –the garments used at that time to comply with laws governing veiling conventions. After that, women were instructed to appear at official gatherings, movie theaters and state institutions without veils. According to historians, there were even signs stating that it was forbidden for veiled women to move beyond certain points in the capital city. Amanullah’s wife, Queen Soraya, was the first woman to appear in public without a veil, announcing that the coverings impaired a woman’s ability to breathe. Some women with no inclination to remove their veils were dismayed and shocked, while others welcomed the chance to throw off the cumbersome cloth. Unfortunately, many women suffered even greater social exclusion as a result of this decree: not only were they no longer allowed to visit cinemas, state institutions and public meetings, they sometimes weren’t even allowed to leave the house.

Sayyida Bibi is a one-hundred-year-old woman and likely one of the few remaining individuals who experienced this reform in person. She remembers the repercussions of the announcement as follows: “We lived in Kabul. My father worked in the offices of the government of Amanullah Khan and had worked at the court of his father as well. In the streets and at the bazaar, rumors were circulating that the new king had ordered women to bare their faces. Some women whose husbands and fathers worked for the government obeyed the government decree. They removed their chador and shed tears of joy. My mother was among this group of women. But some women didn’t receive permission from their families to remove their veil. This meant they could no longer go outside. There were rumors that government officials were removing women’s chadors by force on the street.” These reforms ultimately posed too much of a threat to the interests of mullahs, politicians and authoritarian forces; they created the foundation for revolts and eventually led to the fall of Amanullah.

Amanullah was succeeded by Habibullah Kalakani, a man who began his career as a simple soldier at Amanullah’s court. He is said to have later engaged in a life of robbery and banditry, all in the name of religion. Soon thereafter, he was able to incite a revolt with support from foreign groups, ultimately taking the reins of office. During the nine months in which he served as Emir of Afghanistan, the rules changed once again: the veil became mandatory for women, schools for girls were shut down and women were allowed to leave the house only when accompanied by a man. All of Amanullah’s reform measures were suspended and declared invalid. In other words, women were once again forced out of society and back into the veil. That is, until Mohammad Zahir Shah ascended to the throne.

Mohammad Zahir Shah waited for the perfect moment to cautiously facilitate women’s reentry into society. At the Independence Day celebrations of 1959, the women of the royal family appeared without veils. Compulsory veiling laws were subsequently rolled back once again, striking fear into the hearts of countless women in the country. Many of the women who had come to accept wearing a veil as their destiny had, after so many years, also come to view it as a form of protection, something they could safely hide behind. My grandmother told me that some women found it difficult to remove the veil without feeling exposed.

Before her passing, my grandmother described a particular event during that era: Zahir Shah had invited all government officials to his palace, including her grandfather, who was one of his officials. The aim of the celebration was to lift the veil and thus render female government employees more visible in the social sphere. Because her grandfather didn’t want to lose his job, he decided to take her along with him. But first he showed her a picture from an Iranian magazine and told her to dress like the women in the magazine. She had always worn traditional clothes – a loose dress, white embroidered pants and a veil – and was worried that she would have to remove her veil and attend a prominent ceremony in a dress and nylon stockings. At that time, hair salons were not very common and there were maybe one or two in the entire city where women could get their hair and makeup done. She had worn her hair tied up in a bun all her life. But now she was expected to know exactly how she should get her hair styled without becoming a laughing stock in the process. She decided to style her hair like the women wearing thin headscarves. On the day of the celebration, she removed her regular clothes and put on the nylon stockings and knee-length dress her husband had laid out for her in advance. To spare herself the ridicule of neighbors, she wore a chador over the dress. She wrapped the front of the chador tightly around her body so that no one would notice her stockings and bare legs.

For years after that, women asked themselves how, exactly, they were supposed to dress outside the home. The clothing choices of some women were mocked by members of the upper class or by girls who dressed in clothing popular in other countries. Nylon stockings were very fashionable at the time and they made women’s legs look beautiful. Instead of embroidered pants, many women wore these stockings with their traditional clothing – never forgetting their chador as well. As my grandmother explained it, this way of dressing – which conformed neither to Islamic nor to European standards – was interesting and quite fun.

After the volatile reign of Zahir Shah, the era of the republic began. At this point, women were accustomed to a fashionable way of dressing, and veils were rarely seen in the cities. Each successive president had introduced concessions that expanded the scope of freedom, which turned out to be an effective strategy for achieving political goals. Women held ministerial posts but no one cared much about them carrying out their jobs.

Things continued this way until 1992, when the Mujahedeen conquered Afghanistan, transforming the democratic state into an Islamic republic. The issue of women’s participation in society and their manner of dress was, in fact, a means of gaining political power. The Mujahedeen was aware of this, prompting them to decree that women wear the black hijab traditionally worn by Arab women. As a sign of gratitude for Arab support during the jihad, they propagated this garment, declaring that no girl or woman would be allowed to leave her home without a headscarf or chador. In all the chaos and confusion surrounding the issue of veiling, Afghan women now found themselves back at a point they thought they’d moved beyond 62 years earlier, during the rule of Habibullah Kalakani.

Afghan women experienced these new laws regarding veiling and social participation as the height of injustice. There’s no way they could have known then that the Taliban would soon enter the political stage and force them to wear the hijab. In 1996, the Mujahedeen government crumbled under the weight of greed and capricious behavior. The Taliban marched into the capital, shuttered all girls’ schools and restricted women’s freedom of movement. They forcibly and mercilessly removed women from all areas of social life. The only exceptions to these rules were female doctors and nurses, who were nevertheless subjected to strict religious scrutiny and often beaten when they didn’t comply with veiling decrees. My mother was working in the department of health education at the time. She was beaten with a whip several times and came home time and again with swollen shoulders and arms.

With the advent of the interim government and the inauguration of Hamid Karzai, the first president after the end of the Taliban’s reign, the likelihood increased that women’s veiling would become optional, as the new constitution did not explicitly mention the veil or women’s clothing. The women of Afghanistan then proceeded to take off their chadors, but didn’t dare remove their headscarves as well. Twenty years passed amid excitement and hope that democracy would prevail and women’s rights be defended. Unfortunately, as the saying goes, good intentions are not enough! The Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan – a difficult pill to swallow for most of us – means that the country’s women are once again subject to terrible oppression. For them, the wheel of fate has turned once more, this time coming to a halt on the diktat to wear black clothes.

To protect the author’s anonymity, Parand is a pseudonym. This article first appeared on ZEIT Online on Jan. 6, 2023.